The History of the I&M Canal

The opening of the Illinois & Michigan Canal in 1848 made Chicago and northern Illinois the key hub of mid-America. The canal was a dream hundreds of years in the making, first written down in a European language by Louis Joliet in 1674 but considered long before that by the Native Americans who had inhabited the area for centuries.

With the realization of that dream, great changes became a reality. Canal communities sprouted. Chicago grew into a major metropolis. Agricultural and industrial innovations abounded and Illinois, to this day, is the most populous inland American state. All of that is attributable to the 96-mile canal that linked the Great Lakes to the Illinois and Mississippi rivers.

The Final Link To An All-Water Route

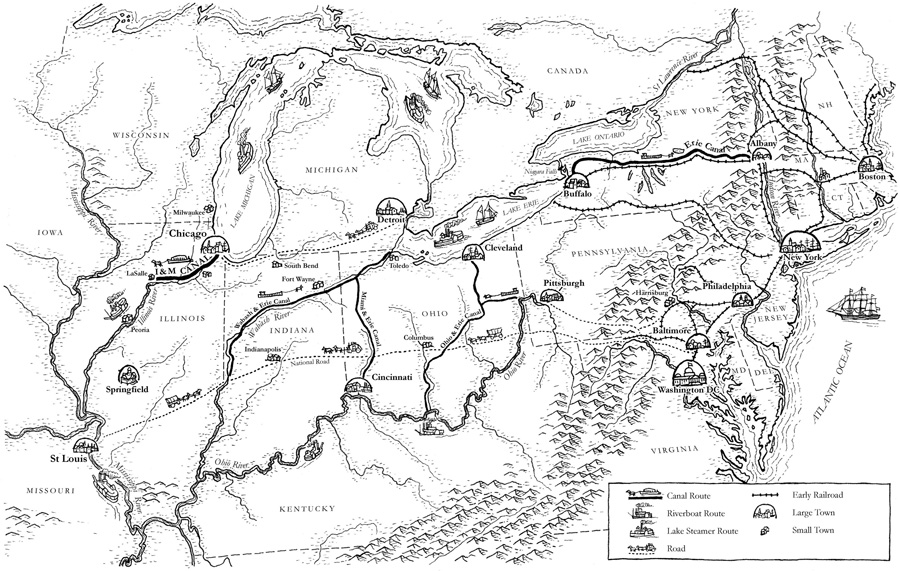

In 1825, the Erie Canal was completed. This 363-mile, man-made waterway connected the Hudson River at Albany to the Great Lakes at Buffalo, opening up water travel between the Atlantic Ocean and East Coast to the Great Lakes region.

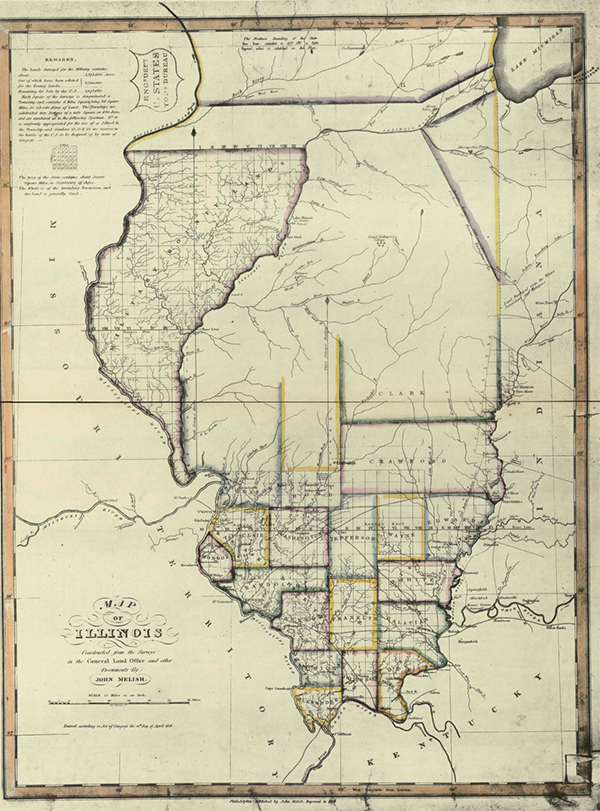

The success of the Erie Canal led to the Canal Era, and northern Illinois became an obvious choice for breaking ground. By constructing just a 96-mile canal (about a fourth the size of the Erie Canal), the state could connect Lake Michigan to the Illinois River, which in turn led into the Mississippi River and then the Gulf of Mexico.

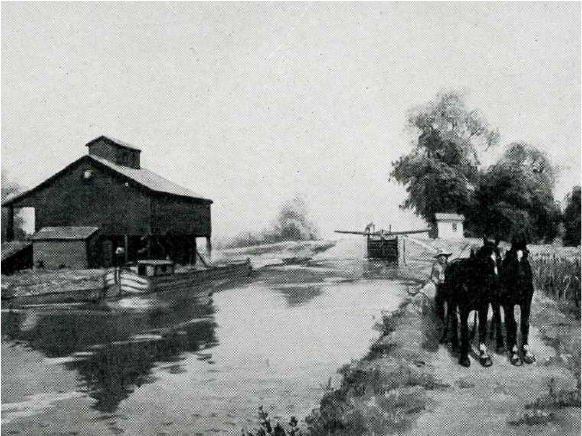

Construction was started on July 4, 1836. It was hoped that the massive public works project, the greatest in Illinois’ young history (it was only granted statehood in 1818), would only take a few years. But, mismanagement, economic depressions and grueling labor (the canal was dug by hand by poorly paid laborers) delayed the project twelve years, and the canal wasn’t opened until April of 1848.

A New Transportation Corridor

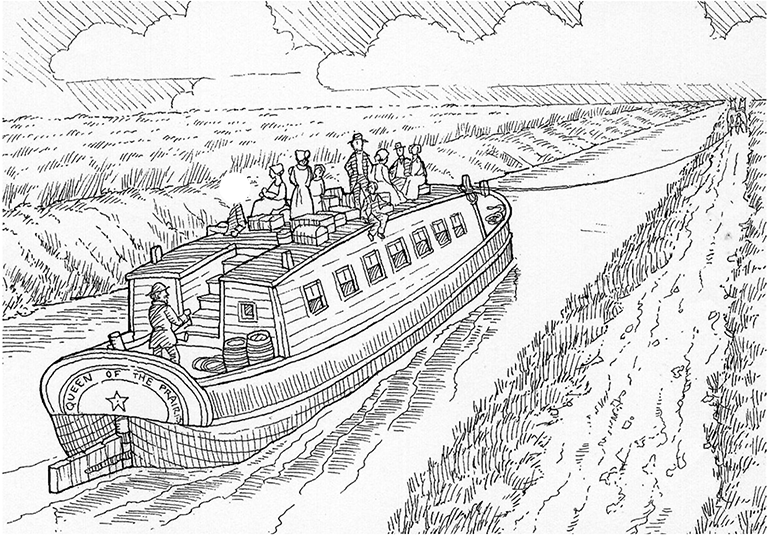

By connecting the waters of the Illinois River with those of Lake Michigan, the Illinois & Michigan Canal (which is named for these two bodies of water) made possible a vast all-water route that connected the East, South and Northwest (note that at this time Illinois was considered “Northwest”). Travelers from the eastern United States could take the Hudson to Albany and then the Erie Canal to Buffalo, where steamboats brought them through the Great Lakes to Chicago and then canal boats brought them along the I&M Canal to LaSalle/Peru. Here people boarded river steamers bound for St. Louis and New Orleans.

The canal stretched from Chicago to LaSalle. It was a minimum sixty feet wide, though several areas known as widewaters were twice that width. The canal’s minimum depth was six feet, though again, there were areas that greatly exceeded that. Though we often think of Illinois as flat, there is a 141-foot change in elevation between Lake Michigan and the Illinois River, which necessitated a series of 17 locks along the route. Canal travel was closed during the winter months, a factor that gave later railroad expansion into the region a leg up (though it would take a few decades before railroads would overtake the canal as a preferred transportation method).

The opening of the canal heralded a new era in trade and travel for the entire nation. Thanks to this all-water route, freight could move from St. Louis to New York in 12 days and at a much more cost effective rate. In comparison, the overland Ohio River Route might take 30-40 days. Passengers also increasingly chose the water route, both for its time-savings and its comfort in providing a steady, less-jostling, mud and dust-free trip.

The Impact of the I&M Canal

Before the first shovel even broke ground, the canal had an impact on the surrounding area. In 1818, when discussions were held over Illinois’ borders and bid for statehood, plans were already in place for a canal. The original Illinois border would have been 40 miles south of Lake Michigan. This would have necessitated the future canal running across two eventual states, an undesirable situation that could have led to strife. Using this to their advantage, Illinois Territory statesmen, like Nathaniel Pope, successfully negotiated to extend Illinois’ border to include nearly 50 miles of Lake Michigan, ensuring Chicago–which was almost a part of Wisconsin–remained in Illinois.

In 1827, the Federal Government granted the state of Illinois nearly 300,000 acres of prime land along the route of the canal, the sale of which would finance the canal’s construction. When the I&M commissioners began selling this land, thousands of people began settling along the line of the canal, realizing the American Dream of owning property and growing communities. Once the canal was open, these canal towns would rapidly expand into the 60 communities that make up our National Heritage Area today.

Of course, the canal had the biggest impact on Chicago. Pre-1848, Chicago consisted of a lonely military outpost (Fort Dearborn) situated in a swamp. It was barely a town and no match for St. Louis, a bustling hub of Mississippi-River travel. The canal helped bring Chicago its first telegraph line, linking the city to the East and first railroad as well as for the first time enabling goods from the South (such as sugar, salt, molasses, tobacco and oranges) to make their way to Chicago. In anticipation of the increased trade that would run through the city, the canal also can be credited with the establishment of the Chicago Board of Trade. Thanks to all of these factors, Chicago surged ahead of St. Louis in population and prosperity. Illinois grew along with the city. In 1850, Illinois was the eleventh most populous state. Ten years later it was fourth.

The canal also played a key component in countless historical events. For one, it was a major element in westward expansion. For instance, those who traveled to California in the 1849 Gold Rush usually spent part of their journey on an I&M Canal Boat. The canal also played a factor in the Civil War. Though early proponents of the canal hoped it would help make the different regions of the country more economically interdependent (and thus stave off conflict), when war did finally erupt, the canal was crucial in transporting government grain and oats toll free to Union soldiers.

The End Of An Era And The Beginning Of The National Heritage Area

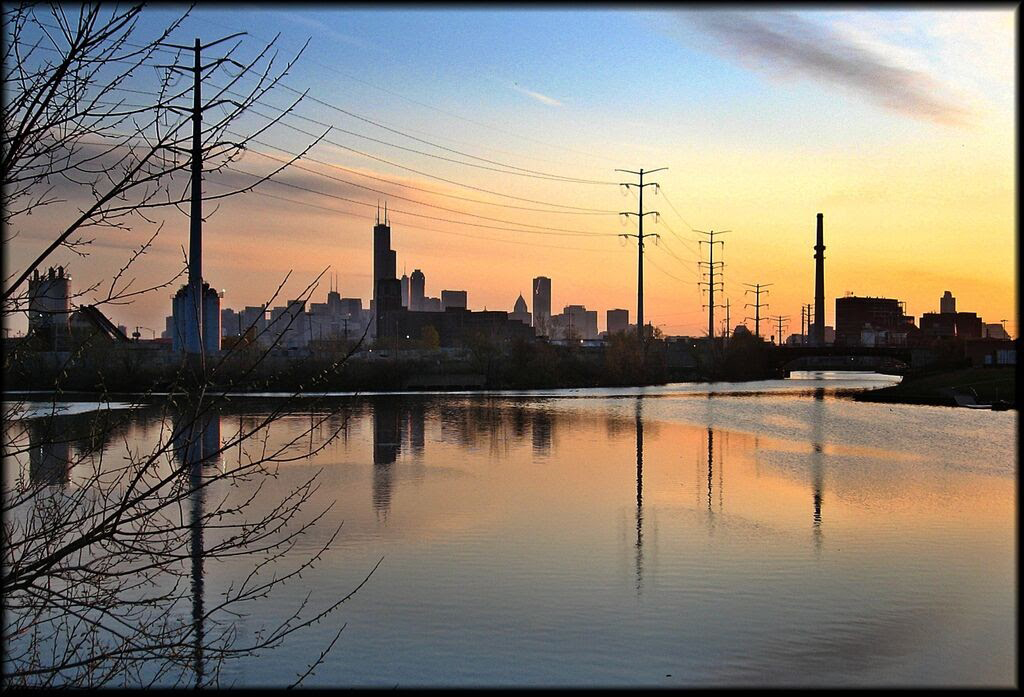

The I&M Canal remained open for traffic for 85 years; however, in the 1890s, traffic declined dramatically. While locomotives had been nipping at the heels of the canal for decades (though the canal can be credited for forcing the railroad companies to keep their rates low, another canal benefit), it was the opening of the larger and more modern Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal in 1900 that spelled the end for the I&M Canal. In 1933, the canal was closed. Ultimately, the I&M Canal was a bridge between waterways and eras, providing Chicago and Illinois the boost they needed until future innovations came along to continue to support their growth.

Today, we recognize the I&M Canal and the communities it fostered for their historical, economic and cultural significance. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan, native son of Illinois, also recognized that significance and signed a bill that established the region as the first National Heritage Area. You can read more about that here >

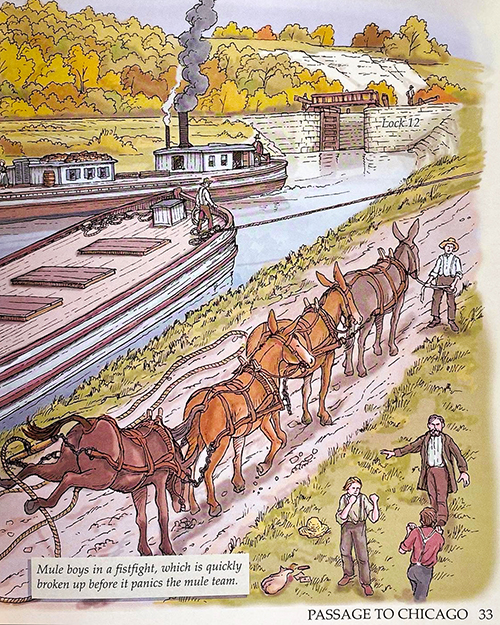

To discover more about the history of the canal, check out the hundreds of stories we’ve collected, featuring such great historical figures as Abraham Lincoln to such humorous anecdotes as Mule Boys fighting along the canal route.

Roadmap for the Future

On December 29, 2011 the National Park Service approved the Illinois & Michigan Canal National Heritage Area’s management plan, A Roadmap for the Future. Beginning in 2012 the Alliance Committee in coordination with the Canal Corridor Association began implementing the plan. Each year the Alliance Committee selects which projects and programs will be implemented or continued to achieve the goals of the IMCNHA. Click on the links below to read the plan or download the PDFs.